A class action case filed in federal court claims that African-American detectives in the New York Police Department (NYPD) are illegally excluded from higher-level promotions within the detective rank (aka the glass ceiling).

The lawsuit asserts that the NYPD unlawfully denied promotions to African-American detectives within the Intelligence Division of the NYPD. The lead plaintiffs are Jon McCollum and Roland Stephens, as well as Sara Coleman, widow of Theodore Coleman.

“I hit a brick wall when it came to my career in Intel,” said Detective Stephens. “I came to the painful realization that my skin color mattered more than my skills and achievements.”

The case is Coleman, et al. v. The City of New York, et al., 1:17-cv-07265, (S.D.N.Y.).

The plaintiffs are represented by Emery Celli Brinkerhoff & Abady LLP and the New York Civil Liberties Union.

The NYPD is represented by the New York City Law Department.

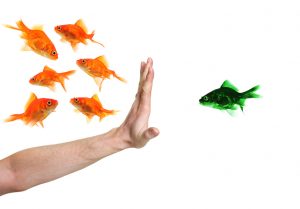

Glass ceiling/promotion discrimination

Glass ceiling discrimination generally refers to an unfair, artificial barrier that prevents certain employees (women; people of color; LGBT) from fairly competing for upper management jobs. In practice, it keeps qualified employees from reaching their full potential and, depending on applicable law, illegally blocks them from occupying the best-paid and most powerful positions. The glass ceiling can be caused by, among other things:

- entrenched attitudes/stereotypes about what type(s) of people should get the “top” jobs;

- subjective/hard to define qualifications for promotions that introduce conscious or unconscious biases into decision-making; and/or

- a lack of networking and mentoring opportunities for women, people of color, and other underrepresented groups

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as well as other federal and state laws, make it illegal for an employer to use promotion practices that create a glass ceiling.

Background about the NYPD’s alleged glass ceiling

The crux of the case is laid out in the first paragraph of the complaint, which states, “[f]or well over a decade, the NYPD’s Intelligence Division has implemented a secretive and unstructured promotions policy, administered by white supervisors who refuse to promote deserving African-Americans detectives.” It continues that, “[a]s a result of these policies, Named Plaintiffs and other African-American detectives have been repeatedly denied well-deserved promotions—even when recommended by their direct supervisors—without explanation, while less qualified white detectives have been promoted above them.”

Each of the three named plaintiffs joined the Intelligence Division in 2001 and helped with the cleanup and investigation of the September 11 attacks. According to a press release, they “tracked hundreds of leads and suspects. In spite of their achievements and strong recommendations from their direct supervisors, they were repeatedly passed up for promotion because of their race.”

Each of the three named plaintiffs joined the Intelligence Division in 2001 and helped with the cleanup and investigation of the September 11 attacks. According to a press release, they “tracked hundreds of leads and suspects. In spite of their achievements and strong recommendations from their direct supervisors, they were repeatedly passed up for promotion because of their race.”

“I watched countless white detectives from my class move up in rank, but not me,” recalled Detective McCollum. “Multiple supervisors told me if I were white I would have been promoted.”

The promotion selection process

The complaint paints a picture of a highly subjective promotion process that occurs in a vacuum. For example, the plaintiffs claim that:

- “The NYPD does not publish when promotion decisions for Intelligence Division detectives will be made, who will participate in the decision-making process, or what weight, if any, supervisor recommendations will be given”

- “Candidates for promotion are not told how many vacancies there are, who else they are competing against, or what criteria will be used to decide promotions. Often, they are not even informed that they are being considered for promotion.”

- “In practice, promotions are the result of a highly subjective decision-making process, with decisions about advancement made in secret by all-white high level supervisors.”

African-American representation in the Intelligence Division

The plaintiffs describe the Intelligence Division as “one of the most elite and prestigious divisions within the NYPD.” As of 2013, the unit employed approximately 600 people, including about 280 detectives.

As to the proportion of African-American employees, at the time the EEOC charge of discrimination was filed in 2011:

- AfricanAmericans constituted 18% of all NYPD police officers and 16% of all NYPD detectives, but only 6% of Intelligence Division personnel and 7% of Intelligence Division detectives.

- White officers were substantially overrepresented in the Intelligence Division,constituting 80% of the Intelligence Division and 80% of Intelligence Division detectives but 50% of all NYPD officers and 57% of all detectives.

“At higher levels of seniority, in 2011,” the complaint says that “there were no African Americans above the rank of Sergeant—in other words, no African American Lieutenants, Captains, or other high-level supervisory personnel—in the entire Intelligence Division.”

These numbers have apparently improved since then, but plaintiffs assert that African-American detectives continue to lag behind their white counterparts.

Class action versus an individual case

An individual case involves one employee (Joe Smith) suing his employer for glass ceiling/promotion discrimination. The way the company treats its other employees will be relevant in an individual case. But the focus of the case and the available remedies will remain on what happened to Joe Smith. Individual lawsuits are far more common than class action lawsuits.

Class action cases, on the other hand, involve a lead plaintiff(s) who, along with the lawyer for the class, represent the interests of a larger group of class members who have been harmed by the company in some common way. Class actions can range in size from 20-30 individuals to thousands of people.

The NYPD glass ceiling case is filed as a class action and seeks to represent not only the three named plaintiffs but also, “[a]ll African-American detectives of the NYPD Intelligence Division who, as of December 14, 2008 or later, were not promoted or whose promotions were delayed based on race…”

Ultimately, the court will decide if the case can proceed as a class action under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 or, instead, if the lawsuit must be broken up into a series of smaller cases.

On a related note, Eric Bachman previously served as a lead counsel on a Title VII employment discrimination class action challenging the discriminatory hiring practices of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY). He led a team of lawyers over several years in litigating this federal court case that involved six Special Masters, dozens of court opinions, multiple expert witnesses, the creation and validation of a new employment test, over a thousand class members, and ultimately resulted in an approximately $100 million settlement.

Hiring an experienced employment discrimination lawyer

Hiring an experienced employment discrimination lawyer

Hiring a proven and effective advocate is critical to obtaining the maximum recovery in an employment discrimination case. Eric Bachman, Chair of the Firm’s Discrimination Practice, has substantial experience litigating precedent-setting individual and class action discrimination cases. His wins include a $100 million settlement in a disparate impact Title VII class action and a $16 million class action settlement against a major grocery chain. Having served as Special Litigation Counsel in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice and as lead or co-counsel in numerous jury trials, Bachman is trial-tested and ready to fight for you to obtain the relief that you deserve.

Bachman writes frequently on topics related to promotion discrimination, harassment, and other employment discrimination issues at the Glass Ceiling Discrimination Blog.

U.S. News and Best Lawyers® have named Zuckerman Law a Tier 1 firm in Litigation – Labor and Employment in the Washington DC metropolitan area. Contact us today to find out how we can help you. To schedule a preliminary consultation, click here or call us at (202) 769-1681 or (202) 262-8959.