The Supreme Court has been asked to decide an issue that has sowed confusion among the various appellate courts around the country: can a single workplace use of the N-word constitute a hostile work environment under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?

This legal question arises during a long overdue reckoning about how to address systemic racial discrimination in this country. Indeed, an employee in one case, Collier v. Dallas County Hospital District, has specifically requested that the Supreme Court decide this issue.

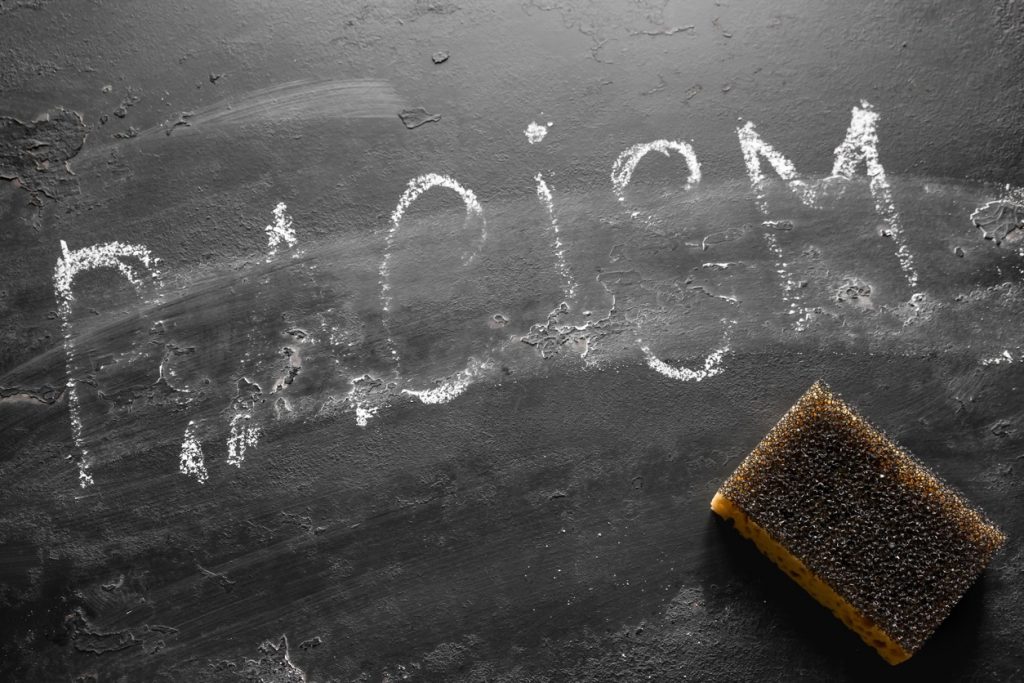

The N-word “sums up . . . all the bitter years of insult and struggle in America, [is] pure anathema to African-Americans, and [is] probably the most offensive word in English.” These words were spoken by Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in a case he decided years ago while still serving on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. The N-word slur is a “singularly odious epithet” that “reminds [Black Americans] of an unshakeable ‘otherness,’ an outsider status in the larger social, economic, and political dynamics of a given society.” Michele Goodwin, N***** and the Construction of Citizenship, 76 Temp. L. Rev. 129, 141 (2003).

Yet the different federal appellate courts are divided on whether the single use of a reprehensible racial epithet, such as the N-word, is sufficiently severe to violate Title VII. This is why it is important for the Supreme Court to address the issue head on and provide clarity for the lower courts.

Background About The Collier Case

The plaintiff/employee, Robert Collier, filed a petition with the Supreme Court earlier this year asking it to review a decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The summary of facts below are taken from the brief filed with the Supreme Court on Collier’s behalf.

Collier worked for the Dallas County Hospital District (Parkland) from 2009 to 2016. During this time, he says he repeatedly complained to Parkland about “racially hostile graffiti” including the N-word etched into the wall of an elevator that he and other employees regularly used. Despite Collier’s reporting the graffiti to human resources, he alleges that it remained in the elevator for at least six months. Collier further complained to human resources about large swastikas that were painted on the wall of a storage room, which he maintains were not removed for nearly two years. Finally, Collier asserts that he objected that white employees called him and other Black workers “boy.”

The Fifth Circuit ruled that use of the N-word was not severe enough to create a hostile work environment in violation of Title VII, and Collier is now attempting to appeal this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework For A Hostile Work Environment Claim

T o prove a hostile work environment under Title VII, an employee must show they were subjected to harassment that is “sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of the victim’s employment and create an abusive working environment.” Meritor Sav. Bank, FSB v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 67 (1986). Later Supreme Court decisions on the “severe or pervasive” standard have held that “mere utterance of an … epithet which engenders offensive feelings in an employee” is not enough. Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17, 21 (1993). But then the Supreme Court subsequently noted that an isolated, albeit serious, incident could be severe enough to establish a hostile work environment. Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775, 788 (1998). As a result, the Supreme Court has never clarified whether saying the N-word at work is simply a “mere utterance” or instead if its use can amount to a hostile work environment.

o prove a hostile work environment under Title VII, an employee must show they were subjected to harassment that is “sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of the victim’s employment and create an abusive working environment.” Meritor Sav. Bank, FSB v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 67 (1986). Later Supreme Court decisions on the “severe or pervasive” standard have held that “mere utterance of an … epithet which engenders offensive feelings in an employee” is not enough. Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17, 21 (1993). But then the Supreme Court subsequently noted that an isolated, albeit serious, incident could be severe enough to establish a hostile work environment. Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775, 788 (1998). As a result, the Supreme Court has never clarified whether saying the N-word at work is simply a “mere utterance” or instead if its use can amount to a hostile work environment.

A Contradictory Patchwork Of Appellate Decisions

The Supreme Court’s muddled approach about what actions may be sufficiently severe to create a hostile work environment has resulted in a deep split among the various federal circuit courts of appeal. In two of the thirteen federal courts of appeal, a single use of the N-word at work can establish a hostile work environment claim. But in at least five other federal courts of appeal (the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 10th Circuits), the courts routinely find that a hostile work environment cannot be proven by a single use of the N-word.

Put another way, appellate courts covering 23 states regularly rule that a jury of an employee’s peers is not even allowed to hear evidence about whether a single use of the N-word could constitute a hostile work environment. In theory, if an employee’s senior manager used the N-word in a workplace meeting but it happened only one time, then, according to the appellate courts covering almost half of this country a jury would not be permitted to decide if this amounts to a hostile work environment. All of this helps to show why the Collier appeal is an important case to watch and why Supreme Court guidance on this issue is needed.